May 5, 2015Taken from http://www.discusnada.org

Introduction

Breeding discus can be one of the most rewarding aspects of the Hobby. At the same time it can also be one of the most frustrating. There is nothing more beautiful and unique than the way discus care for their young. The biggest piece of advice I can offer anyone is patience! A well conditioned pair will breed over and over again, until they have a successful spawn, so if all does not go well, relax, normally in 5-9 days they will spawn again.

Selecting and conditioning the breeding pair

There are a few ways to go about this; the quickest is to buy a proven breeding pair from a quality retailer. Proven means that the pair has successfully spawned and some of the eggs have hatched (insuring you have a male and female). It doesn’t necessarily always mean that the pair has actually successfully raised a batch of fry however. Expect to pay a premium price for a healthy attractive pair. If this is your first attempt at breeding, I strongly recommend a non-albino or non-pigeon blood pair. Some of the easier strains to start with are the darker brown based fish such as Virgin reds or Red covers, or a nice Turquoise pair.

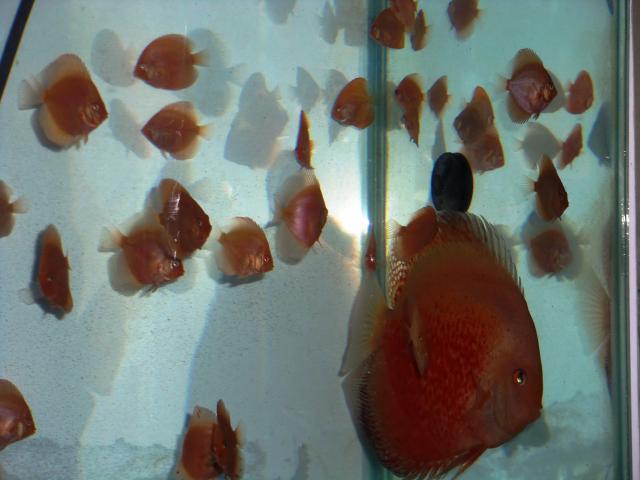

If you’re in no hurry, another option is to buy a group of 5 or more juvenile fish, and grow them out to adulthood (this gives the new hobbyist must needed experience in successfully keeping discus as well). Hopefully, as the fish mature, a pair or two will form from this grouping. Make sure to keep this group of the same or compatible strains (mixing strains is generally frowned upon for beginners and may result in ugly unsellable offspring).

Females will start to hit maturity anywhere from 9-14 months; males can take a bit longer. It is not uncommon for two young females to pair up together, so don’t assume just because two of your young fish are together and one is laying eggs, one is a female and the other a male. There are many myths out there regarding how to successfully sex discus, but the most reliable is to have a good look at the breeding tubes (and even this sometimes fools even the most advanced hobbyist). The female breeding tube (ovipositor) tends to be larger and blunt at the tip, while the males are smaller and comes to a point.

Make sure your selected pair is healthy, well fed, and free from any disease. Try to select fish that are at least 5 ½” (female) to 6”+ (male). Things like white feces, fin rot, and overly thin fish should not be allowed to breed. The same applies to fish that seem to flash or scrape themselves against tank objects on a regular basis. I like to feed my pairs only the best of foods, and as often as they want prior to introducing them into the breeding tank. Breeding can be quite stressful for the pair, and only the healthiest should be allowed to breed.

Courtship

The pre-spawn rituals of a mated pair of Discus can be quite the sight to behold. They can be go on for a few days, or be quite brief, every pair is a bit different. One of the more fascinating “dances” you may witness is the “bow”. This is when the Male and female face each other some distance apart near the bottom of the tank, and simultaneously both swim upwards at a 45 degree angle towards each other. When they have met, they will then proceed downward, again at a 45 degree angle, until they each occupy the others beginning position.

They will also begin to look for a suitable breeding surface, and begin to clean the area, both taking turns pecking at the surface. As the spawn becomes closer, they will “tremble” as if they were shivering. When you start to see this, a spawn is nearing.

Once your pair(s) has formed in the community tank, and you’re reasonably sure you have a male and female, let them practice a bit before rushing them into a breeding tank. This helps to form a strong bond between the pair and hopefully will help to avoid problems with the two fighting when moved to the breeding tank. Don’t worry; if the first spawn is not successful (and it won’t be in a community tank) they will spawn again in the next 5-9 days.

This is also a good time to mention that Discus do not pair for life. You can mix and match pairings, and even force a pairing when necessary. For Discus, breeding is instinctual and not emotional.

Setting up the breeding tank

Once you are reasonable sure you have a good pair (or you purchased a proven pair) it is time to set up a breeding tank. This is not an option, but rather a necessity. Your chances of having a successful spawn and be able to raise the fry all within the confines of a community tank are slightly less than winning the lottery. Many people will panic when, after keeping a group of discus in a community tank, they witness their first batch of eggs. They fill the need to try to “save” the eggs and go to some extreme measure to try to suddenly adjust the tank by adding dividers etc in an effort to isolate the pair. Don’t bother. Enjoy the show and start making plans to do thing the right way if you decide you want to try your hand at breeding.

First you want a breeding tank, typically a 20 or 29 gallon tank, or even a 40. Myself, I prefer the 29’s. In this tank you will want a sponge filter, a heater, a breeding cone, and possibly a light, nothing else. Breeding tanks do not require a lot of light, and too much will be counter-productive. If your tank is in a spot where it receives some natural sunlight and you have a room light you can leave on at night, chances are you won’t need one at all. If you do opt for a light, to dim it down you can block a good portion of it of with cardboard, ,just make sure it doesn’t get to hot. You will want to paint or apply a light background of some sort to the bottom and three sides. Avoid dark colors as they will make attachment much harder for the newly born fry.

Water requirements (part 1)

While domestic discus will live in and thrive in a variety of water (providing it’s clean and stable), breeding does require some special conditions. Of major concern is the water “softness”. Discus can seldom breed successfully in “hard” water. With the possible exception of wilds, Ph on the other hand is not as much of a concern (although we will initially monitor it), just so long as the water is soft (low on calcium content). While some of us are blessed with water naturally soft at the tap, most of us will need to purchase an RO system, and a TDS (total dissolved solids) meter. Feel free to try for a go or two with your tap water (I recommend at least a TDS meter to test your tap) but chances are you are going to need an RO system. The reason why is that hard water tends to interact with the outer surface of the discus egg, causing it to calcify, and then the embryo will suffocate. In extreme cases it has even been reported that hard water will prevent the eggs from becoming fertilized. Test your tap water with a TDS meter, and chances are that if your TDS is above 100, you are going to need RO water. For a good explanation of how to set up an RO unit, and how it functions, as well as the TDS meter see this article here:

For More Information on RO Units, Click Here!

Water requirements (part 2)

So now that our RO unit is up and functioning, we want to soften our tank water so the pair can be successful. I found 80 ppm TDS to be a good starting point. After preheating our storage container of RO water to 82 degrees, we want to measure its TDS. If our unit is functioning properly the TDS should be in the 8-20 ppm range. We then want to buffer this water. We can do this quite simply by adding back just enough of the RO waste water back into the RO water to bring our TDS back up to 80 ppm, or we can add one of the commercially available buffering products available such as Kent RO Right. Either will work, but I find the latter a bit of a waste of money myself. We will also make a point to monitor Ph, until we learn our water. What we want to guard against is a PH crash. This occurs when the buffering capability of the water gets so low, that the minerals that impact Ph are quickly depleted, causing the Ph to nose dive. Discus can adjust to quite well to a range of Ph’s but they will not tolerate a crash. Typically this will not happen until the TDS level gets below 30- 40 ppm, but due to the fact everyone’s water supply is different, it is important to monitor until you are comfortable this will not happen.

If, after a try or two at a TDS of 80 ppm, we find we are still having trouble getting a hatch, or our hatch rate is unsatisfactory, we will try again by lowering the TDS to 60, then 40 if necessary, always remember to monitor Ph each time you drop your TDS, until you are comfortable you will not experience a Ph crash.

If we get as low as 35-40 and we still have no hatch, chances are that we either have two females in the breeding tank, or the male is not doing his job (making runs), is infertile, or is just too young.

One word about learning your water. Do not get too discouraged should you hear others make statements on how they get great hatch rates at a certain TDS that is much higher then yours. Unless you are on the same water supply, this information is largely irrelevant. The reason for this is that the mineral elements that are responsible for the total dissolved solids in the water are not just limited to Calcium and magnesium (the two elements largely responsible for hard water, but other trace elements such as mineral elements as well. So while the guy that is claiming he gets great hatch rates at a TDS of 110 might very well be telling the truth, the simple fact is you may have more calcium in your water which is showing a TDS reading of 60.

The Spawn

Now that we have the pair in the breeding tank, and we have our water softened, we let nature take its course. Tank temperature should be at or around 82 degrees, the tank is at reasonably quiet location in the house (to much activity in a busy room should be avoided) and daily water changes of 50%+ are being made. If you have just moved the pair into the tank it is not unusual for the pair not spawn right away (although often they will) and they might go “off cycle” for a week or two. As soon as they have settled and they find the tank to their liking, it will be business as usual. Be sure to include a spawning surface such as a breeding cone, section of PVC pipe, clay flower pot, or some other suitable spawning surface (I prefer the cones). Once the pair begins their normal courtship ritual anew, you can expect eggs in a few days. Just prior to the spawn the pair will begin pecking at the breeding surface “cleaning” it. They will sit side by side shaking and shimmying and start to make dry runs over the breeding surface.

After a few passes, the dry runs will no longer be dry runs and the female will start to deposit her eggs that will attach to the breeding surface, the male will watch (and hopefully not eat the eggs) as she makes a run or two and then he will make a run himself over the eggs covering the eggs in milt. This process will play itself over and over for a few hours until the pair is done.

At this juncture we have a few decisions to make, or simply do nothing. For the first few attempts I prefer to do nothing, but it is not unusual for a young pair to eat the eggs prior to them hatching, or even after they have hatched. If this happens, and continues to happen for an extended period of time, you may opt to screen the eggs. This will prevent the pair from getting to the eggs until they hatch and the fry goes free swimming.

Hopefully given the time to observe the eggs, then the hatch, the pair will “bond” to the fry and be less apt to eat them. A simple screen can be made from some fine meshed plastic fencing or “gutter guard”, weighted down and placed around the breeding cone.

Another thing some choose to do is to add some methylene blue to help prevent the eggs from being over run with egg fungus. I do this myself, although others choose not too. If you opt to use the meth blue, frequent water changes will remove it from the water and I aim to have it almost completely removed prior to the hatch, which typically happens 52-56 hours after the spawn. Another option is to add some activated carbon to a HOB filter, this is fine, however I prefer to remove the HOB filter prior to the free swim.

The hatch

Somewhere around 52-56 hours after the spawn the eggs will begin to hatch. The fry will look like tiny little tadpoles and will still be stuck to the breeding surface at the head. Occasionally a fry or two will fall from the cone and the male of female will retrieve the fry and “spit” them back on to the cone. At this time the fry are referred to as wigglers or wrigglers, as they will do just that, wiggle while attached to the cone. It is after this time we can slowly begin to transition the tank water away from soft water to harder water. I prefer to up the TDS 20-30 ppm with each water change until the tank water is completely transitioned away from RO water. As time progress’s and 48 hours elapses from the hatch, fry will start to “escape” and start to swim off. The parents will frantically work together to capture the escapees and spit them back onto the cone.

Free swimming and Attachment

At around the 48-56 hour mark after the hatch more and more fry will begin to leave the cone as the parents’ frantically work to keep them there. Eventually the parents will give up, or decide it’s time to let the fry free. You will soon have fry scattered about the tank everywhere. This is the stage in which the fry are considered “born”. This is also the stage that can be the most frustrating. When things go wrong (other than not getting a hatch) it will happen at this stage. What we want to happen is for all the fry to be attracted to the parents, who at this stage should have become much darker than normal (this is to attract the fry) and begin feeding off of the parents slime coat. The fry never actually “attach” to the parents, rather they stay extremely close, less then a millimeter away, and continually bite at the parents, feeding from the parents slime coat.

However, the fry can become lost, often stuck in the corner of the tank, or attracted not to the parents, but the sponge filter. If this continues for a long period of time (24 hours+) the fry will begin to starve and die off. It is also extremely hard to perform a water change with fry scattered about the tank. For this reason I stop feeding the parents 24 hours after the hatch and make sure to keep the tank in pristine condition. I have been changing water regularly up until this point. With any luck, all the fry will attach to the parents without help, but lending a helping hand is not uncommon. To that end there are several things you can do.

- Lower the water level. To do this and not suck up any fry in the process I will use an airline tubing with airstone attached. I will then slowly siphon off the water into a five gallon pail until the water level is about ½ full.

- Pull the sponge filter, or wrap in a white cheese cloth. This will remove obstacles and distraction for the fry, making the parents the only dark object in the tank. If you pull the sponge, be sure to add an airline and airstone into the tank, but keep the air flow low.

- Dim the lights. Cover up a good portion of the light with cardboard or foil making the area around the cone (this is where the parents typically are) the darkest part of the tank.

- Patience. Don’t over react. To much activity around the tank will only stress the parents and might cause them to eat their fry. Give them time. Many times the best thing to do is to ignore the tank completely and let nature takes it’s course. Remember, if this batch is unsuccessful, we most likely will have a new batch and the parents will have more experience in a week or so.

Feeding your new fry

At about three days free swimming we want to set up a brine shrimp hatchery.

There are many ways to do this, but I use a 20 gallon tank with a few bricks inside it. I fill the tank about ½ full of water, add a heater and heat the water to about 80-82 degrees. I then take 2-3 2 liter soda bottles, cut the bottom off them and clean them well. I will fill these bottles about 2/3 full of RO waste water(tap is fine as long as your water is hard) and add 2 tablespoons of salt. What salt doesn’t matter, you can add table salt, aquarium salt, water softener salt (make sure if you go this route it is solar salt without additives), or as I use, canning salt. Then add an airline to the 2 liter bottle with a slow but steady stream of air. We do not want to “boil” the water, but we do want to keep it circulated. Then add your brine shrimp eggs. Make sure there is a good source of light over the hatchery, a simple clamp on incandescent bulb or overhanging fluorescent will work just fine. In 24 hours you will have freshly hatched baby brine shrimp, IMO the best food source for baby discus. Yes there are several alternatives to freshly hatched baby brine shrimp; some swear by them, most swear at them.

When your brine shrimp has hatched, remove the air stone and let sit for about one minute. This will allow the un-hatched eggs to float to the surface. Many people will choose to use a light to the side of the hatchery tank to congregate the BBS (they are attracted to light like a moth). You can then either use a turkey baster to suck up a few good batches of BBS, or you can siphon the fry out via a airline tube and into a brine shrimp strainer. I have done it both ways, but prefer the strainer method.

Then simply add the BBS to the breeding tank. At first it will be hard to tell if the fry are eating the BBS, but within a few days there will be no question about it. Depending on how large the batch of fry I like to have at least two batches of brine shrimp made a day, one for the morning and one for the evening. I will typically get two feedings out of each (for a total of 4 feedings a day). For larger batches I may have three 2 liters bottles going, each started at different times of the day.

The reason why we have multiple batches of BBS going set to hatch at different times of the day are simple. When a brine shrimp is first hatched from its egg, it has a yolk sac. This is the source of nutrition for the brine shrimp for the first several hours, and also the source of nutrition for the baby discus. As the yolk sac is used up by the baby brine shrimp, it loses all its nutritional value for our baby discus fry.

During this time while we are feeding baby brine shrimp, it is imperative to keep up on our water changes. 50% daily is a bare minimum, 80% twice daily is better. Also do frequent tank wipe downs and pull and clean your sponge filter regularly. Failure to do so will result in catastrophe. This can not be stressed enough. Once disease sets in, there is very little you can do to save your fry while they are young. The answer is prevention. I cannot stress this enough. This is the part that most people screw up on.

Separating from parents

The parents can be pulled from the fry as early as when they are readily eating BBS, but I prefer to leave them in the tank a while longer. This can change however when I have an extremely large batch of fry and the parents are taking a beating. With medium and smaller batches, there is no reason to pull them so long as the parents do not look stressed. If the parents, however, start courting each other again, acting as if they are about to spawn again, pull them immediately, or the fry will get eaten as the parents prepare to spawn again. I prefer to see my fry start to transition to solid foods before I remove the parents. While with young, I am normally feeding the parents freeze dried blackworms (FDBW) cubes pressed against the glass. At about two weeks the fry, which have grown at an incredible rate, start to take interest in the parents’ food and less and less interest in the BBS. By three-four weeks I have transitioned completely away from BBS and I am feeding a micro pellet, some flake, and some Beefheart. This is when I typically pull the parents.

The importance of clean water-lots of it.

The importance of water changes during the grow out phase for baby discus can not be overstated. We have a whole lot of fish in a small area. We have parents producing excess slime to feed the young fry. We are dumping in gobs of BBS to feed the fry as well. All of this and the fact BBS if left uneaten in the tank can spoil in a hurry and lead to all sorts of protozoan and bacterial issues in the tank. You cannot skip a day of tank maintenance and expect to have success. Breeding discus is not hard, but it is hard work.

Growth rates

Expect to get about ¾ to 1” of growth per month. This will vary a bit as different strains have different growth rates, but it is a good rule of thumb. It is not, however, an absolute that can be applied to all discus. There are a few strains such as goldens an albino’s that do tend to grow at a slower rate.

Culling

One of the necessary evils of raising discus is the importance of culling. Obvious deformities and mal-formed fish should be continually culled and destroyed. This process usually starts at 4-6 weeks can continue up until the three to 4 month stage. At this point, if you have done your job properly, you should be finished. Please don’t unload your less than ideal fry on the general public for discount prices or even for free. This does nothing good for the advancement of the hobby!

What to do with all these fish!

This article is from North American Discus Association. www.discusnada.com